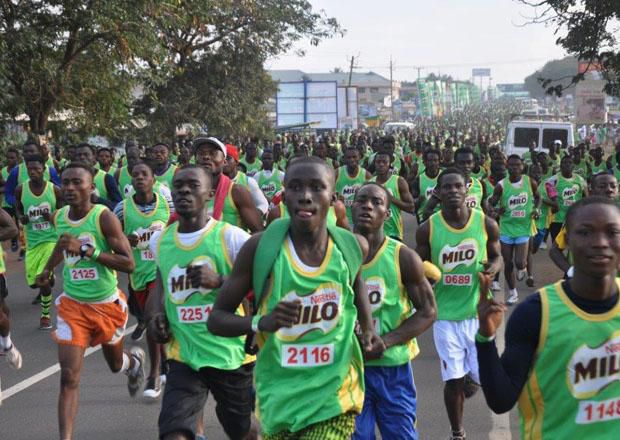

In 2005, the Accra Milo Marathon would see one of its keenest climaxes ever. The final laps were all kinds of competitive and paradoxical: veteran versus rookie, legend against prodigy, master contra apprentice… Then-three-time winner David Zigah head-to-head with 18-year-old Godwin Adukpo.

The marathon would go down to the wire and a fairytale triumph would be birthed when the rookie beat the master to the finish line. But more than just an underdog story, it would also signal a paradigm shift on the local scene; the transfer of the torch from one torchbearer to another.

Adukpo had adored and idolised Zigah for many years. As a boy growing up in the village in the Volta Region, he wanted to be the next Zigah. So to be in the same race with his idol was a dream come true. “When the marathon started, I was only looking for Zigah,” Adupko recalls in an exclusive interview with Pulse.com.gh.

And so having trailed Zigah for large spells, the youngster couldn’t believe his luck when he finally spotted his mentor with 15 kilometres left.

“When I finally saw him, I started following him. Wherever he went, I tagged along,” recounts Adukpo. “I followed him till Korle-Bu, where a random guy on a bicycle whispered to me that Zigah was tired and that that was my chance to overtake him.

“I watched Zigah’s face but nothing showed he was tired. I didn’t believe he was tiring. In my mind, he was invincible. But as we raced shoulder by shoulder, everybody we encountered on the way was signalling to me that Zigah was tired. I decided to heed them and make my move.

“I dashed forward in anticipation that he’d match my pace. But he didn’t. So I increased the pace. He still wasn’t closing in, so I left him behind and sped off. For the first time I felt I had it in my hands. And I went on to win the race.”

Adukpo became the youngest winner in the senior category of the Accra Milo Marathon, completing the 42.2km race with a time of 2:29.29. Zigah would ultimately finish third after being overtaken by Victor Ashiagbor, with just a minute separating the two.

---

Adukpo, now 36 and retired, was born in Dzita, a fishing community in the Volta Region of Ghana, where children tend to fish rather than go to school. Adukpo himself didn’t have the luxury of attending elementary school after losing his parents at a very young age.

This left him, and his twin sister, fending for themselves as they lived with their grandmother, who equally had many mouths to feed since she was taking care of other children. As a way of making some extra money, Adukpo divided his time between trawling on the sea and running errands for elders in the community.

The reward for those errands? On good days, he would receive money and other gifts from his benefactors. On not-so-good days, however, leftovers were all he could lay hands on.

“Growing up was tough because we lost our parents at a young age,” said Adukpo. “When people send me to buy something for them, I run as fast as I can. The trick was that whenever I returned early, the person was likely to ask me to keep the change.

“Or if it was food, they’d eat and leave some for me to eat. So I tried to impress whenever anyone sent me on an errand by going fast and returning early. That's how we were surviving.”

Despite the lush sceneries in Dzita, the town is often in the news for being ravaged by tidal waves, which leaves many residents displaced and properties destroyed yearly. For kids, this sort of repeated turbulence denies them any form of stability in their growth.

As if having to contend with all that, as well as missing the presence and tenderness of his parents, wasn’t difficult enough, Adukpo would also be separated from his twin sister, who needed to leave the village to preserve her own future. “My twin sister had to be sent to Akosombo [in Eastern Ghana] because over here [in Dzita], when you grow up to a certain level and you are not going to school, they force you to do certain jobs.”

Running errands became a coping mechanism for young Adukpo and, in doing that, he would develop a passion for sprinting. For free spirits, though, passion can be a euphemism for boundless energy and Adukpo began feeling the power that comes with focusing on what excites him. The more he ran, the more he got better at it and built up his stamina, albeit in oblivion.

“I was more of an errand boy, and they [used to] send us a lot at the beach,” says Adukpo, a memory that makes him grin.

---

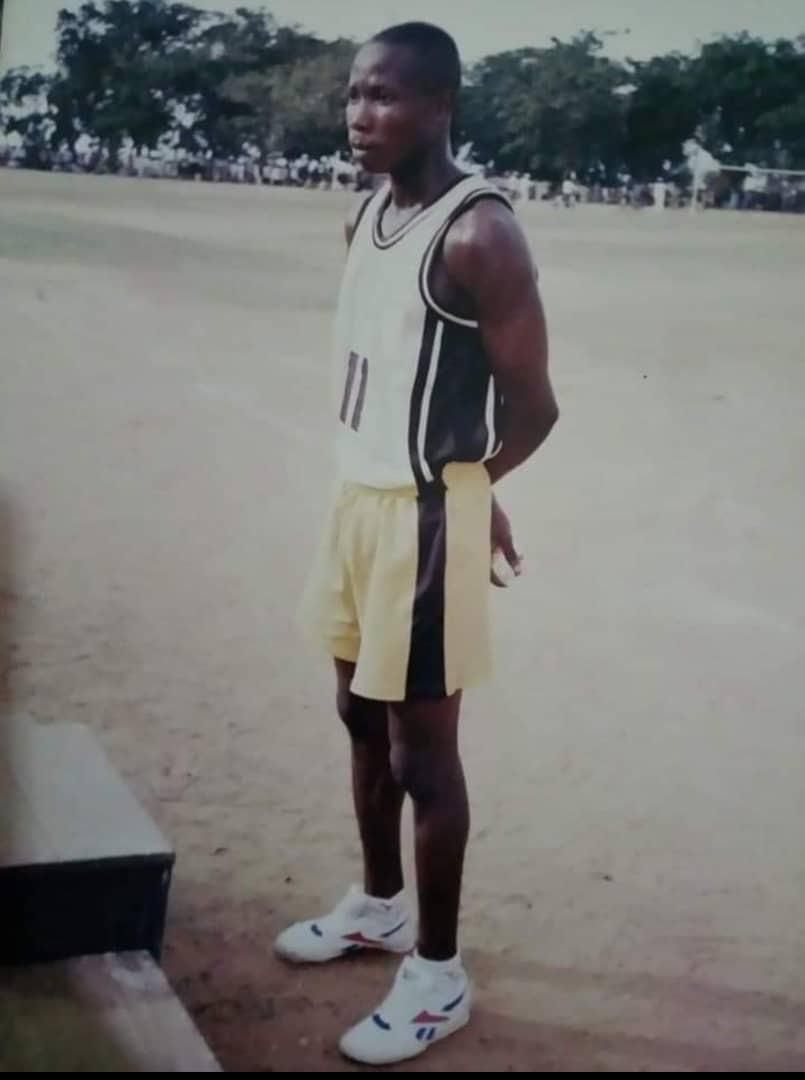

Even with no proper training, running around made Adukpo peppy and vibrant. He was confident too, and his self-belief would lead him to challenge some students of Dzita LA Basic School who were having an outdoor PE lesson to a race during one of his random errands.

An audacious Adukpo approached the PE teacher and told him he could do better than his students. “He was initially reluctant because I wasn’t a student of the school, but I was daring and I told him if he gave me a chance, I’d disgrace the other students in a running contest,” he said.

Luckily for Adukpo, his bluff caught the attention of the PE teacher, who invited him to join the next session, where he competed in the 100m, 200m, 800m and 1500m and excelled in all the races.

“When I went, I was instructed to run the 100m race, but I wanted to do the long distance,” Adukpo said. “At my first attempt, I came second in the 100m, then I was asked to do 200m. Then they allowed me to join the 800m race – the pitch was quite small so we went round the park four times – and I finished first. I competed in the 1500m next and I won that one too. That was how I proved myself.”

That was how Adukpo officially got introduced to athletics and, in the years that followed, he would carve a career that saw him become one of the best marathoners from Ghana.

For over a decade, he dominated the local scene, going on to win the Accra Milo Marathon four times – just one shy of his mentor Zigah, who holds the record as the competition's greatest athlete with five winners’ medals – but it all started with bluffing his way into a race.

It is, however, one thing to run errands at a fast pace and entirely another to compete in races. Adukpo’s success story on the PE grounds, however, piqued his interest and he started nursing the idea of becoming a professional athlete.

With every race he won, his name began spreading like wildfire in the community. He had identified his niche as a long-distance runner and he was excelling there. Such was Adukpo’s level of competitiveness that the teachers begged his grandmother to allow him to spend more time with the school’s athletics team, rather than on the fishing boats.

She would reluctantly agree to their plea and Adukpo quickly went from merely training with students of the school to representing the school in competitions despite officially not being a registered student. He was winning too.

“I represented them in several inter-school competitions, winning the 800m and 1500m contests,” he recalls. “I proceeded to inter-area competitions and won there too. Then I represented them in inter-zonals and even at the district level.

“When I returned, they asked me to officially join the school. So I started schooling, but I had to divide my time between class and fishing, since I needed to make some money for my survival.”

---

Long before Adukpo’s keen rivalry with Zigah was birthed at the national level, his first taste of a marathon adversary came while he was still fledgling in the village of Dzita.

At the time, his longest distance was 1500m but he had outgrown his competitors, having won the inter-regional competition in Kumasi while setting a new record in the process. Even though he was just 15, his talent excited many in his community and it wasn’t long before he was encouraged to take on his older colleagues in the 5000m and cross country.

But there was already a champion in the aforementioned categories and his name was Joseph Yandall. Yandall was already a household name in the Volta Region, where Adukpo hails from, and was clearly the better athlete at the time. He had also won the U-15 category of the Milo Marathon in 2002 and was the region’s brightest prospect due to his impeccable record in competitions.

The rivalry was on, and not many were backing Adukpo to handle the step-up well, let alone usurp the region’s marathon champion. But that is exactly what he would do.

“When I started running the 5000m and cross country, I usually finished second to Joseph Yandall until 2004 when I was finally able to overtake him and I also dominated from there,” effuses Adukpo, who can’t hide his pride as he speaks.

One regret Adukpo has from his amateur years was that, unlike Yandall, he never got the opportunity to compete in the U-15 category of the Milo Marathon. Despite being an adolescent boy, the years of working at sea had taken its toll. He looked older than his actual age, which always led to his disqualification from the junior marathon, which was reserved for adolescent kids and early teenagers.

“Some of us, they would just look at our faces and say you are old, so they disqualify us. They say under 15, but they don't ask us of our age,” Adukpo recounts. “They were doing that to me continuously, so in 2003 when they disqualified me, I said I wasn’t going to accept it. So I joined the senior Milo Marathon. In my first attempt, I finished 30th. And I realised the distance was longer than in the junior contest. In the junior contest, we trained for just 15 km, but the senior contest was almost 42km.

“I stopped on the way several times before I got to the finishing point but, even by finishing 30th, I was given a lot of products from the sponsors so that motivated me. After that, I started training hard towards the next year’s race.”

Those disqualifications from the junior marathon annoyed Adukpo and, although he made the decision to start competing in the senior category, he wasn’t quite ready yet. Finishing 30th, though, was a sign that he could do it if only he trained harder.

So that was exactly what Adukpo did. Buoyed by an innate will and determination to win the Accra Milo Marathon, he moved to Akatsi to train day and night on the mountains.

“Sometimes, I ran from my village to Akatsi and back,” he said. “Other times, I can run from my village to Aflao and come back. These distances weren’t easy but I was doing that just to build myself towards the following year’s marathon. So the following year, in 2004, I finished eighth.”

Adukpo continued to train hard and his hard work would eventually pay off when he beat Zigah to win the Accra Milo Marathon for the first time in 2005. That year’s race was the archetypal David vs. Goliath contest.

Here was Zigah, then winner of the marathon three consecutive times in 2001, 2002 and 2003, against Adukpo, whose highest finish in the national competition was then eighth. In fact, when the duo first met two years prior, Adukpo was left star-struck after sighting his mentor.

“I was hearing of David Zigah, but 2003 was when I really saw him,” he narrates. “I was actually tailing him during the race but at a point he left us and went ahead to finish first. Later, I looked for him and began asking for tips on how to win the marathon.

“Initially, he wasn’t really forthcoming but I kept disturbing him. Anywhere I saw him, I’d go closer to him and ask ‘How do you do it? I want to be like you’. So he told me his secret was training hard.

“I started varying my training. I started running on hills, running at the beach. I was desperate to win the marathon. Fortunately, I completed Junior High School that year, so I decided to dedicate all my time towards training. I was not doing anything else. I was just training every day. At a point I was sleeping at the Ho Sports Stadium alone.”

For a boy who had to overcome adversity all through his childhood, fate would have it that he went through one more hurdle en route to becoming a national champion. Giving his all in training made him so confident ahead of the 2005 marathon but even his trainers didn’t foresee him getting a podium finish. “They all doubted me,” Adukpo smiles as he harks back to those moments.

But the real distress came in the hours leading to the marathon. When Adukpo made the journey from the Volta Region to Accra to compete, he knew nobody in the capital and so had nowhere to sleep. He arrived a day before the race, late in the night, and went around begging people in a bid to find a place to rest. He didn’t find any.

Refuge eventually came, albeit belatedly, and he would spend that night in the unlikeliest of places – on a shaky bench with his eyes open until sunrise.

“No one was ready to help so I made my way to the starting point of the race and I met a guy who was looking after the place. I engaged him in a chat and told him I was going to win the race. I was doing that to convince him to allow me to sleep at the starting point, although that wasn’t allowed,” Adukpo recounts.

“So I waited and when everyone left, I put some benches together and laid on them. I couldn’t sleep that night until morning.”

He couldn’t sleep but once he was at the starting point, Adukpo knew there was no turning back. He applied everything he learned during his training; he made a fast start to the marathon, slowed down midway to catch his breath and when he finally caught up with Zigah, he never let him out of his sight.

---

Beating Zigah to win the Milo Marathon in 2005 was the moment Adukpo etched his name in the hearts and minds of Ghanaian marathon lovers. And although he went on to win the marathon three more times, his first triumph was what gave him street credibility.

The reception back home and across the country was special too. “I was received like a king,” says Adukpo, who is almost blushing as he relives that victorious moment. “Aside from the prizes and cash after winning the Marathon in 2005, a lot of people also gave me money. Several big people, chiefs hosted me in their palaces, and I visited the Regional Minister too.”

With that came along a scholarship to attend Anlo Secondary School, where Adukpo continued to compete in several marathons. He’d, however, have to wait for three years to become a national marathon champion for the second time.

He had near misses in 2006 and 2007, but returned strongly to win the marathon three consecutive times in 2008, 2009 and 2010. He may have matched Zigah’s three-peat, but rues his failure to beat his rival’s five overall titles.

Part of that was due to an injury he suffered on the eve of the marathon in 2009. Adukpo was travelling when he got involved in a car accident. His knee was rocked from the crash but, as defending champion of the Milo Marathon, he decided to compete despite the injury.

He went on to win the race that year but aggravated the injury and it would prove costly in the following years and would ultimately force him into an early retirement in 2017.

“I wanted to break Zigah’s record of five wins in the marathon. Unfortunately, I had a car accident in 2009 which affected my knee. I was advised not to participate in the marathon that year but I still did and I won. Nobody knew I was injured,” he said.

“When I went back to the hospital, the doctor was afraid that I could lose my leg, but he treated me and I returned to win the marathon again in 2010. But after that the pain returned. Till now, whenever I run long distances, my knee locks at some point.”

In his prime, Adukpo was a beast but the injuries just wouldn’t allow him to reach his full potential. He was also a bit stubborn and overconfident, and his ego sometimes got in the way. And for that, his career overall remains in the ‘what could’ve been’ category.

For instance, even when he was outgrowing his comfort zone, he refused to work under professional coaches. He believed in himself so much – and, perhaps, he was too loyal to those he began with – that he felt his childhood trainers and PE teachers were best placed to take him to the zenith of his career. How wrong he was.

“I was not under any professional coach before I won the marathon and a lot of people were saying I would do better if I worked with a coach,” Adukpo owns up. “At a point, I was asked to join Zigah’s coach but I rejected it. I was still relying on my secondary school PE teachers and those who brought me up for training.”

Even at that, he represented Ghana in several international marathons in Mali, Malaysia and the Netherlands, and realised his childhood dream of competing against marathon legends like Haile Gebrselassie, Eliud Kipchoge and Kenenisa Bekele in his prime.

---

Athletics in Ghana has seen very little development in recent years. And while the country has produced some promising athletes in 100m, 200m and 800m, long-distance runners remain in short supply.

The Accra Milo Marathon, which used to be the most prestigious marathon in the country and served as a warm-up for athletes preparing for international contests, has been halted since 2016.

Even worse, facilities where athletes can train are in short supply, especially in the capital, after the tartan tracks at the Accra Sports Stadium were removed as part of renovation works towards Ghana hosting the 2008 AFCON. Adukpo believes that singular act killed athletics in the country.

“Athletics in Ghana died in 2008 when the country was preparing to host the AFCON,” he articulates. “The Accra Sports Stadium used to have tartan tracks but they were removed while renovating the stadium for the tournament. That rendered Accra trackless because El-Wak is for the military and it’s not standard. So athletes in Accra have to struggle to get a place to train. It’s why athletes in Kumasi started doing better than those in Accra because Kumasi has the tartan tracks.

“The government has to take a look at the management of the sport if we want to produce better long-distance runners. There should be a plan on how to bring up young runners. As we speak, in the whole year, they have just two competitions and that is not good enough.”

These days Adukpo is into public service. He may not have risen to international acclaim, but he ruled the streets in his prime and his name is the stuff of legend among locals who keenly follow athletics. He remains an icon to a whole generation of Ghanaians; those who were born in the mid-to-late-1990s and early 2000s. For they saw him come from nothing and do it all by upsetting the odds and endearing himself to them.

In his own rendition of a victory dance, Adukpo had his own famous victory sidesteps. Each time he won the marathon, he would run a few more metres beyond the finish line – a message to his rivals that he still had more fuel in his tank. Anytime he did it, a crescendo of applause greeted him as he took in all the glory.

After retiring, he became a Customs Officer, where he currently holds the rank of Revenue Assistant Grade 1, and is in charge of training new recruits.

But athletics remains in his blood. When he has time on his hands, he works as an athletics coach and physical training instructor; nurturing persons who want to carve careers in the sport and follow in his footsteps.

Adukpo’s advice to young ones who want to dominate the athletics scene, though, is simple: “If you want to succeed in whatever field, be it long distance or short distance, you have to be ready to sacrifice a lot. You don’t wait to hear about a competition before you start training. A good athlete trains all the time.”

)

)

)

)

)